This, combined with our spirit of entrepreneurship has led to generations of new arrivals from culturally and linguistically diverse (CaLD) backgrounds establishing successful small businesses to contribute to our economy and enrich our community.

Every day Western Australians frequent these small businesses, whether it’s learning a new skill picking up a tasty treat for dinner or buying and selling real estate. The contributions of CaLD business owners to our state are many, and include:

- Providing job opportunities for Western Australians

- Creating links between WA and overseas markets

- Supporting fellow WA businesses

- Providing unique goods and services as well as driving innovation and sharing new ideas.

This report aims to better understand the representation and contribution of CaLD business owners in WA and collect insights from their experiences to inform policies, programs and services.

Data in this report was derived from the following sources unless otherwise indicated:

- ABS Customised Report 2020 based on the 2016 Census of Population and Housing and 2019 Counts of Australian Businesses

- 34 in-depth interviews with CaLD small business owners conducted in English across September to November 2020 (please treat qualitative insights as directional).

People from CaLD backgrounds are defined in this report as per ABS guidelines using multiple indicators including country of birth, ancestry and main language other than English spoken at home, to capture the cultural and linguistic characteristics of

a person. Specifically, the focus of this study is on small business owners residing in Western Australia with 0-19 employees who themselves or whose parents were born in a non-main English-speaking country (NMESC). NMESC include all countries except

the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, United States of America and South Africa.

About the Office of Multicultural Interests (OMI)

OMI develops strategies that include everyone — culturally diverse communities, the wider community, business and industry groups, government and non-government agencies — to help develop a society that values and maximises the benefits of

its cultural diversity. Its strategies assist organisations to develop policies, programs and services that are accessible and responsive to the needs of a diverse community.

OMI provides information, advice, funding, training and support to communities and community organisations to help build strong communities that maintain and share their diverse cultures and participate actively in all aspects of Western Australian life.

The WA government proudly acknowledges and celebrates our cultural diversity as one of our state’s great strengths and actively plans for a future that captures its potential.

The CaLD business landscape

As of June 2019, there were an estimated 226,416 small businesses in WA1, out of which 35,720 were owned by people from CaLD backgrounds.

- 226,416 small businesses in WA1

- 78.8% small businesses located in Greater Perth 1

- 66.3% small businesses that are sole traders 1

- 35,720 CaLD small business owners in WA

- 79.1% CaLD small business owners located in Greater Perth

- 58.7% CaLD small business owners that are sole traders.

Compared with Western Australian small business owners, CaLD small business owners are more likely to be employers.

CaLD small business owners by country of birth

- People of Italian, Indian and Chinese origin account for the top 3 CaLD small business owners.

- Residents of Italian (28.4%) and Dutch (22.0%) origin had the highest propensity to start a business, while residents of Singaporean (3.6%) and Zimbabwean (2.8%) origin were least likely to set up a business, based on the number of CaLD small business

owners by country of birth, compared to the number of WA estimated resident population2 for the same nationality.

Counts of WA CaLD small business owners by country of birth of parents

- Italy 6231

- India 3329

- China3 2581

- Netherlands 2283

- Malaysia 1702

- Germany 1311

- Vietnam 1771

- Singapore 587

- South Korea 546

- Zimbabwe 391

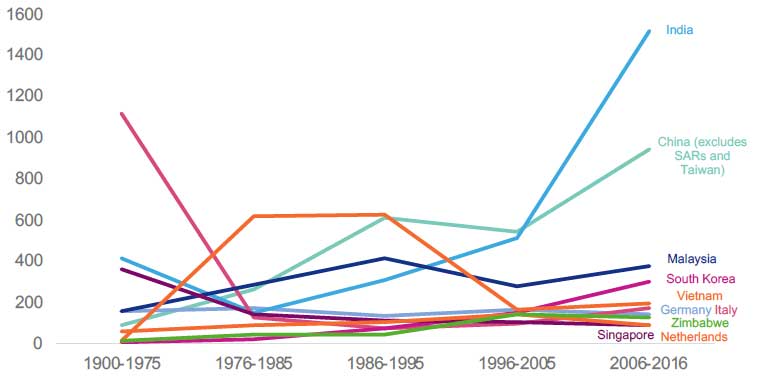

CaLD small business owners by year of arrival

The biggest cohort of CaLD small business owners in WA arrived within the last 10 years, with recent arrivals led by Indian and Chinese small business owners.

4

Table A1

Percentage of CaLD small business owners in WA

| Time | Percentage |

|---|

| Before 1976 | 17.3% |

| 1976 to 1985 | 12.9% |

| 1986 to 1995 | 19.8% |

| 1996 to 2005 | 19.8% |

| 2006 to 2016 | 28.6% |

The majority of Italian-born business owners arrived before 1975. The drop in arrivals in the 1970s coincided with Italy experiencing economic buoyancy, prompting many Italians to remain in Italy.5

The peak of Vietnamese arrivals between 1975 to 1985 coincided with refugee settlement followed by family reunions after the end of the Vietnam War. The decline in arrivals in the 1990s coincided with the implementation of the Comprehensive Plan

of Action for Indochinese Refugees and streamlining of the Vietnamese Family Migration Program.6

The rise of Chinese arrivals in the mid-1980s coincided with the commencement of the Australian government’s active marketing of educational services in Asia.7

The dramatic increase of migration from India between 2006 to 2016 coincided with the surge in education-related and skilled migration during the period of significant labour shortages across the economy during Australia’s mining boom. 8

CaLD small business owners by age and gender

Most CaLD small business owners in WA are aged between 45 and 54 years which aligns with the overall WA business community with 27.9% of small business owners between ages 45 and 54 years.

9 Small business owners from Indian and South Korean backgrounds tend to be younger.

- 15-24 2.4%

- 25-34 19.2%

- 35-44 15.4%

- 45-54 31.7%

- 55-64 22.8%

- 65+ 8.5%

Top age group by country of origin

- India 25 to 34 years old 38.5%

- Vietnam 45 to 54 years old 36.5%

- Malaysia 45 to 54 years old 31.0%

- China 45 to 54 years old 31.2%

- Singapore 55 to 64 years old 25.6%

- Germany 45 to 54 years old 37.0%

- Italy 45 to 54 years old 37.5%

- Zimbabwe 45 to 54 years old 29.7%

- Netherlands 45 to 54 years old 36.2%

- South Korea 25 to 34 years old 35.0%

The majority of CaLD small business owners are male, despite the close numbers in the gender split of the estimated resident population of these nationalities. The highest percentage gap between male and female small business owners can be seen in those

with Indian and Italian backgrounds.

By industry, the greatest gender gap is seen in transport, postal, and warehousing industry and construction.

The CaLD business industries

CaLD small business owners by industry

The top industry by number of CaLD small business owners is Construction. Most of these business owners are sole traders and of Italian origin. Similarly, the majority of overall WA small businesses are in construction, with more than half made up of

sole traders.10

As a percentage of total WA small businesses, CaLD small businesses are most highly represented in education, hospitality, and administrative and support services.

Table A3

Top industries by number

| Industry | CaLD small business owners | Small business counts in WA11 |

| Construction | 6039 | 39,265 |

| Professional services | 3820 | 27,633 |

| Transport, postal and warehousing | 3333 | 24,946 |

| Health care and social assistance | 3073 | 21,414 |

| Hospitality | 2720 | 19,243 |

CaLD small business owners are highly represented in the education and training industry.

Table A4

CaLD Business Owners as % of Total Western Australian Business Owners in these Industries

| Industry | Percentage |

|---|

| Education and training | 39.0% |

| Hospitality | 34.0% |

| Administrative and support services | 26.7% |

| Public administration and safety | 26.3% |

| Other services | 25.8% |

Qualitative insights

The findings from interview data

Insights into CaLD small businesses in WA were generated from in-depth interviews with 34 CaLD business owners. The respondents were drawn from the CaLD business community with the help of promotion and snowball sampling.12 They were aged 18

years and above, and either migrated to Australia from non-main English-speaking countries (NMESC) or were second-generation migrants with at least one parent born in a NMESC and were small or medium business owners or co-owners.

Interview questions were designed to explore information such as the respondents’ cultural and linguistic backgrounds, business profile, motivations, and insights from their experiences, including challenges, opportunities and contributions.

Profile: CaLD small businesses and business owners

Of the respondents, 14 (41.2%) were women and 20 (58.8%) were men. Their age varied between 28 and 56 years for women and 35 to 54 years for men. Thus, a large number were in their late forties with the average age estimated at 45 years (Table A2). Similarly,

their ethnic backgrounds also varied. More than two-thirds (23 or 67.6%) of the respondents were of Asian origin, followed by almost one-quarter with European background (eight or 23.5%) and three (9%) were of African descent. While a larger proportion

of men were of South Asian, mainly Indian origin, women were of South-East Asian, particularly Malaysian descent. Most of them had degree-level qualifications (79.4%) with six having postgraduate degrees.

The respondents also have diverse migration histories. Some migrated with their parents when they were young in the 1960s or in the late 1990s, but a sizeable number (17 or 50%) migrated between 2003 and 2016. In terms of business, with a few exceptions,

most of the respondents started their own business recently (less than 10 years ago). Largely, the business industry of these people varied by gender. For example, men were involved in the professional, technical and scientific services, followed

by hospitality (food and accommodation) and real estate industry. While the women’s industry mainly included education and training, language teaching and translation, beauty products and hair or make-up salons. Men were predominantly employers

(18 or 90%) employing between one and 30 people, while most of the women were sole traders (11 or 78.5%).

The respondents’ diverse ethnic backgrounds, migration history, business experience, and industry of business offered varied insights into their motivations, challenges, opportunities and future aspirations, as well as contributions to the WA business

sector. These insights are presented in the following sections.

Motivations of CaLD small business owners

Research shows that in Australia and across the globe, migrants are often motivated to start or take up a business by necessity or after being pushed by negative factors, pulled by positive factors, or by a combination of both. Push factors include adverse

circumstances such as loss of a job, absence of adequate job opportunities or discrimination in the labour market. Pull factors on the other hand, include prospects of having ethnic enclaves that can offer a protective market, greater freedom or control

over own affairs or a spouse who can provide emotional support, adequate expertise and skills, and financial support needed for the business.xiii Whether a person becomes a necessity or opportunity-based entrepreneur depends on many factors, including

family background and family support, cultural factors such as ethnic networks and hard-working culture, level of education and English proficiency, time spent in the destination country and psychological traits such as willingness to take risks.

These, along with external factors such as labour market condition and other supportive policy measures available to migrant communities, impact the decision to start a business.

An analysis of the interviews undertaken as part of this report on the motivations for CaLD business owners supports the broad motivational patterns. These motivations can be broadly categorised as aspirational, opportunity or necessity-driven.14

Aspirational

It should be noted that business aspirations do not develop in a vacuum. A person’s aspiration or ambition can be tied with family tradition and support, having relevant experience or qualifications, or as a pathway to career progression. Entrepreneurial

qualities such as innovativeness, risk-taking aptitude, consideration for freedom or flexibility, can also help shape the desire to owning a business.

Of the interview respondents, the largest number (18 or 52.9%) always aspired to or had adequate skills, experience or qualifications to start their own business. This finding is consistent with the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report that highlights

56.0% of the adult entrepreneurs in Australia considered that they have the skills and knowledge to start a business. 15

Their aspiration was highlighted during the interviews, where respondents shared that running their own business was a long-held dream or desire, sometimes because they grew up in a business-owning family or derived as a result of their skills, qualifications,

experience or a matter of attitude. The following quotes from the respondents help generate greater insights into these links:

We had a family business in India. I invested in a car detailing franchise with my brother. Mainly because it was easy to manage and I saw it as a growing industry. At the time in Perth, there weren’t a lot of car detailing businesses.

— (Respondent

23)

I was doing a job and this is something I’m always interested in. I went through my education and got my license in migration. I just wanted to grow further. Yes, you have to. This is a licensed job, I had to get a certificate of migration. I went

through my English test then I got my license.

— (Respondent 30)

I was VP for a very large company. What that company did was allowed me to learn a lot of skills then I realised I can do a better job and go to business for myself. I was prepared to take the risks and I have a successful business now.

— (Respondent 10)

Yes, I think from a very young age, I’ve always been entrepreneurial.

— (Respondent 24)

Motivations of CaLD small business owners

There were others who wanted to be in business because they were inspired by their friends’success or learning from their parents struggle in finding suitable jobs. This is reflected from the following comments:

[I wanted to] start a business in WA as a friend gave me the idea about how to live in WA and to work better. He runs a business himself in WA and he inspired me. I helped him and my other Thai friends and their families to learn English here in WA. He

told me that if I wanted to do my own teaching, I should have my own business.

— (Respondent 26)

My parents had difficulty in getting an adequate job. I just always wanted to do real estate so didn’t consider other options.

— (Respondent 19)

Freedom, flexibility, spending time with family or child caring opportunities are the other

factors that influenced business aspiration, particularly for women business owners. The following narratives that emerged in response to business motivation illustrates this point:

Because this was the only business I can think of that will be flexible enough for me to still take care of my kids while running it.

— (Respondent 3)

Flexibility and being able to spend time with family.

— (Respondent 34)

Opportunity-driven motivation

There were others who wanted to be in business because they were inspired by their friends’success or learning from their parents struggle in finding suitable jobs. This is reflected from the following comments:

[I wanted to] start a business in WA as a friend gave me the idea about how to live in WA and to work better. He runs a business himself in WA and he inspired me. I helped him and my other Thai friends and their families to learn English here in WA. He

told me that if I wanted to do my own teaching, I should have my own business.

— (Respondent 26)

My parents had difficulty in getting an adequate job. I just always wanted to do real estate so didn’t consider other options.

— (Respondent 19)

Freedom, flexibility, spending time with family or child caring opportunities are the other factors that influenced business aspiration, particularly for women business owners. The following narratives that emerged in response to business motivation illustrates

this point:

Because this was the only business I can think of that will be flexible enough for me to still take care of my kids while running it.

— (Respondent 3)

Flexibility and being able to spend time with family.

— (Respondent 34)

Opportunity-driven motivation

Opportunity-based motivations can be linked to the possibility of leveraging personal skills and abilities, recognising and acting appropriately to the perceived or actual opportunity, making innovations or innovative moves, or ready to take risks or make

changes.

The next largest group of respondents (seven or 20.6%) were mainly driven by opportunities arising from personal experience or qualifications, accidental encounters with relevant people or it ‘just happened’ as there was a demand for the particular

service they were offering or wanted to offer. Quotes from respondents help illustrate this opportunity-driven motivations:

I met a German guy who has been running this for 20 years before me. He was retiring and he asked me if I was interested. We ran it for a year together then I took over and renamed it.

— (Respondent 16)

It kind of just happened. There was no comprehensive Korean school in Perth. Just basics. No reading, history and culture, and I thought, I used to do that in Singapore, why don’t I run my own course here?

— (Respondent 20)

My own situation made me want to work for myself. …My masters degree was in Electronic Engineering. I was taking a PhD in Singapore, but I never finished. At the core, I’m a programmer. I started to understand cloud and security a bit more

and found that a more interesting topic. When I got more clients, I started asking people to be contractors. Then I just shrunk my weekly hours with clients. l would work 2-3 days a week with one, then the other client, I’ll work with for 2

days.

— (Respondent 18)

Motivations of CaLD small business owners

Necessity or push-driven motivation

Push-driven motivations can be linked to many factors such as unemployment or underemployment, career disruption due to childbirth or migration, lack of adequate qualifications or adequate recognition of qualifications, low English language proficiency,

lack of understanding of the host country’s employment or business culture and facing systemic barriers including racial discrimination.

The third largest group (18%) of respondents were motivated by necessity or push factors such as loss of a job, discrimination in the labour market and lack of adequate qualifications to get a job. There was also evidence of lack of job opportunities matching

peoples’ qualifications, along with limited understanding about host country rules and business activities. For example, when asked “Did you always want to be a business owner in Australia? What were your reasons for setting up your business?”,

the following narratives were shared:

I sort of fell into that because I couldn’t get a job. They thought I couldn’t speak English. I was discriminated because of that and I don’t have a degree. So, I decided I’ll just do this.

— (Respondent 2)

After I had my baby, I couldn’t go back to work. I applied but they all said I’m overqualified. I graduated with a Bachelor’s in Commerce in International Business.

— (Respondent 15)

It was my first time to live in a foreign country. I took it as an opportunity to learn more. I thought I’d find a job, but there was less opportunity here, and I couldn’t find a job. I had a different educational background and it’s

not same in other countries. Another hindrance — I couldn’t exactly understand what to do, or how to utilise my educational backgrounds and skills.

— (Respondent 31)

In addition to these three major motivations, it is important to note that a couple of respondents were driven by altruism, a desire to contribute to the society or make a difference. For example:

I worked with international students for 2-4 years. Then I realised, because I’m passionate about this and feel like I’m part of that community, I should help students. Now it’s my bread and butter and I can help people. It’s not

just a business but a profession.

— (Respondent 11)

When I started my full-time career and found out I could make a difference where I was working and I had ideas, I started looking into it [starting my own business].

— (Respondent 14)

The analysis of business motivation narratives presented above highlights the similarities between people from CaLD backgrounds and the wider business-people when it comes to the motivational factors in starting a business. However, certain push factors

such as lack of acknowledgement of overseas qualifications, discrimination and language barrier are more evident for people from CaLD backgrounds. This, along with factors surrounding family tradition, support from family, friends and their community,

also play an important part in CaLD small business owners’ decision-making process.

Challenges experienced by CaLD business owners

Moving to a different country poses many challenges for the individuals and families involved,regardless of their backgrounds. An analysis of the interview responses shows that individuals from CaLD backgrounds experienced a diverse set of challenges

in their entrepreneurial journey. It highlights factors such as personal characteristics and circumstances, as well as institutional or accessibility-related barriers that influenced CaLD business owners’ settlement process or journey to set

up a business in WA.

Personal circumstances or characteristics that were highlighted by respondents as challenges included a lack of local experience and a lack of both professional and personal support networks. In addition, they noted to have encountered differential business

norms and labour market or business practices, as well as racial or other discriminatory behaviour in the process of establishing themselves or their businesses in WA. From an accessibility standpoint, they highlighted difficulty with navigating local

employment and business landscapes due to a lack of easily accessible information, services, and support to start a business for migrants from CaLD backgrounds.

Culture shock, language barriers, racial or other discrimination and unconscious bias

More than half (56%) of respondents experienced issues around culture shock, language-related barriers and discrimination (including unconscious bias) in their journey to start a business. The narratives that emerged from the analysis of interview transcripts

highlights that culture shock was an outcome of different linguistic, cultural or business norms and practices in WA, compared with those of the respondents’ birthplaces or expectations. Accordingly, there was often an overlap between culture

shock, linguistic barriers and racial or other labour market discriminations. The following quotes illustrate these challenges and the inter-linkages:

It was culture shock. Also, at the time I moved to Australia, I wasn’t aware of the world. There was no internet at the time, no social media. It was hard. The challenge was the disconnection with my family. Also, the time difference between Vietnam,

and the language. I had to study English. English was not really popular in Vietnam. It was a brand-new environment, brand new culture, brand new social environment.

— (Respondent 15)

Melbourne is very multicultural. When I came to Perth, which was much later, after five minutes of me presenting, they said ‘You’re English is very good’. There’s still stigma, not as much as before. Australia is very close to

Asia now. In terms of stigma, there’s still a lot of that around. You’re an Asian person, they’ve still got stigma, especially if you’re from Korea or China or Japan. It’s a bit of a shame.

— (Respondent 8)

If you’re not from Perth, the people don’t want to talk to you because you don’t have local experience or local education or local network. Although the people asking themselves are not from here — they’re from the UK! With

big companies, just because I’m not local here and don’t have experience, people just brush you off and make you start from the bottom again. While everybody had to start from somewhere, it puts you 10 years back in your career. If you

have a 457 visa, you’d be 10 years behind your career.

— (Respondent 5)

Challenges experienced by CaLD business owners

It should be noted that the language barriers are not limited to low English proficiency and can be complex and multi-dimensional. These other dimensions include diverse accents or lack of understanding of the jargon used in the business world. These complexities

can be seen in the quotes below:

English was definitely a challenge – I was 18 when I moved here, and I only had a basic grasp of English. Coming here was really hard to cope – lots of jargon and local slang and terms. It took a long time to get up to speed.

— (Respondent 17)

The people making fun of me, of my pronunciation. I just stay away from people who don’t appreciate me for who I am.

— (Respondent 27)

Respondents also reported experiencing disadvantages due to existing racial stereotypes around migrant businesses, limited cultural awareness of people and unconscious bias, as mentioned below:

...it’s very different here in Perth. Settling into the differences. I went from where girls were supposed to wear high heels, now jeans and sneakers. Here you have to say sir to your boss and look up to them as if they are king.

— (Respondent 2)

...but it’s hard at first due to stereotypes of Indian migrants and how they do business. Creating rapport takes time.

— (Respondent 17)

…I wouldn’t call it racism, more like inadvertent bias. The general population don’t see the difference in race unless you’re from a multicultural background. They don’t know how to talk about race, they have good intentions

but say things in their own way. When people say your English is good, people are trying to be nice, and it’s meant as a compliment, but I was raised bilingual.

— (Respondent 4)

Accessibility and network-related challenges

Existing business norms, labour market policies and practices also play important roles in the settlement process for migrant business owners. Many CaLD small business owners (79.4%) experienced institutional or accessibility-related barriers that included

a lack of simple and easily accessible information or advice about business, labour market and relevant services. Additionally, information around funding or grant facilities, support for marketing and networking opportunities were also highlighted

as challenges faced during their entrepreneurial journey in WA. There were sentiments shared by the respondents around WA being a small market and challenges around building trust in a new country or city. The following quotes against the question

“What challenges do you face as a migrant small business owner?” can illustrate these barriers clearly:

Getting the right information from immigration. With the importing business - what needs to be paid, there are no clear rules, those were difficult. There are difficult lingos and paperwork — the legalities. You always have to have a lawyer with you.

— (Respondent

2)

There is no one here to help so you are on your own. No family or network of friends so you have to do it all yourself. Support means advice, guidance, emotional, financial, etc. It’s really hard work and takes a long time but you have to learn

a lot. There’s help with the small business council but if there was someone to ask a quick question to get pointed in the right direction, that would help. With my background, age and experience, it was very hard to get taken seriously. It

took me two years to convince Yagan Square to believe in my plan and take me seriously.

— (Respondent 14)

Challenges experienced by CaLD business owners

Small businesses don’t have much resources, there is no funding for marketing.

— (Respondent 11)

As a small business, cash flow is a challenge, and technology.

— (Respondent 15)

Obviously, when you’ve just opened up, people don’t trust you. You have to advertise a lot. I suppose because sometimes, home businesses don’t work as well. If you have a commercial space, people can walk by and come in. With home businesses,

people have to make an appointment.

— (Respondent 1)

While funding and marketing issues are well acknowledged and common for small business owners in general16, the impact can be greater for migrant business owners. Given that three-quarters of the respondents were first-generation migrants, their

predicament could be easily understood in the absence of credit history, networking and other issues. Research shows immigrants are likely to have smaller and less effective networks compared to other entrepreneurs.17

It’s been hard to find representation in the same industry. I ended up creating my own networking platform. I kept going to networking [events] but no one looked like me.

— (Respondent 32)

While I was starting out, there was setting up and it took two years to get into the community, getting referrals in WA and doing a lot of face-to-face meetings, networking.

— (Respondent 33)

Contributions made by CaLD business owners

It is important to note that being a CaLD migrant does not necessarily mean that people only experience challenges or aren’t able to contribute as part of the wider community. This research identified that most respondents were highly qualified and

resilient. They often turned their challenges into opportunities and overcame their struggles through hard work, patience, existing technical skills and effectively using their links to family, home country markets or social networks. In the process,

they are making huge contributions to the business community and the wider society.

CaLD business owners creating jobs for others

In-depth interviews highlighted that a large majority (67.6%) of the respondents were owner-employers generating employment for one or more people in WA. Additionally, more than half of the respondents (53%) expressed their desire to hire more people when

business conditions improve post COVID-19. Although we cannot generalise these results, it does show that migrant business owners play an important role in job creation, not only for people from CaLD backgrounds, but also Western Australians in general

and help enhance the WA economy. For example:

English is my second language. I think the sooner you accept that fact and the fact that you have a different background, different culture, the better. I hire people locally to do client-facing work, then I have engineers and developers working behind

the scenes. We have some engineers in Australia, but client-facing tasks are handled by people from Australia and UK.

— (Respondent 18)

…we want to support small to medium business owners so they can realise their dream. Once they start, it can become difficult for them. We want to help them realise the dream they had can become a reality.

— (Respondent 11)

Educational background enabling CaLD entrepreneurship

More than half of the respondents (53%) were involved in the professional, scientific and technical services or education and training industries. This could be related to the fact that most of the CaLD business owners were university degree holders (79%),

which helped boost their ambition and confidence to start a business. Additionally, it is worthwhile to note that most of the respondents of Asian origin who now run a business migrated to Australia mainly for educational reasons.

18 For example:

In the next 5 years, I’d like to have a few more people and have different markets. I’d rather not work on the day-to-day things because I’m also studying. I’m doing a Bachelor of Law in Murdoch. I would have to do some training

with a law firm. We want to expand to other areas as well, another branch, separate to the branch and not mixed in with the migration business. My dream is to also have a family law practice. I think it’s also important to the migrant community.

— (Respondent 9)

I am full-time now. I have 2 girls and one is graduating. I teach 6-7 classes per week. I started teaching online for free during the pandemic. I did new things.

— (Respondent 22)

Contributions made by CaLD business owners

Serving as a bridge between the home and host countries

The study highlights that going beyond traditional industries of mining and construction, migrant business owners have ventured into more diversified industries. With the help of family, friends and using their cultural roots as an asset, they serve as

the bridge between their former home and Australia by providing unique goods and services such as education, migration services, ethnic hair styling services, cuisine or cultural entertainment. The following quotes help illustrate this point:

Most of the time you have an advantage if you speak different languages. Clients are more comfortable if you speak their language. Mostly, Indians go to Indians, Chinese go to Chinese. I think they can speak or can explain better to the person they’re

talking to, can understand them and where they’re coming from. I’m quite social in the Indian community. My main market is Indian market, but we also get different nationalities.

— (Respondent 11)

There is no Bengali restaurant that serves Australian fast food. We came up with it. We get ingredients from different cuisines and we experiment with the food to be different from everyone. The Bengali customers come; I get Middle Eastern customers too.

I have a mix of customers.

— (Respondent 27)

...95% of my students are local, the rest are from overseas. Teens who may want to work in Korea. Korea offers a better deal than in Japan.

— (Respondent 20)

It is important that the government organisations supporting small businesses takes cognizance of the changing business landscape and provide necessary support to CaLD business owners to develop and strengthen their business activities and use their

cultural backgrounds and connections as a business advantage.

Working as a conduit of inter-community and inter-generational links and support

Most of the CaLD business owners interviewed provided goods and services to the broader WA community — metropolitan and regional. Thirty out of 34 respondents had local clients or customers from WA, seven did inter-state business and eight also engaged

with international clients. They stated that they often promote Perth as part of their business strategy when dealing with international clients. Nearly all the CaLD small business owners interviewed confirmed they get their supplies locally from

WA businesses and support local manufacturers, suppliers and service providers from diverse backgrounds.

We serve 80 customers every day. Our concept is fine dining, quality fine dining at a low price. About 80% of our clients are local Australians.

— (Respondent 27)

Mostly in WA, some from other states as well. We get regional clients as well. We got clients from Bunbury and other regional areas, mostly because of word of mouth.

— (Respondent 11)

Contributions made by CaLD business owners

Two in every five CaLD small business owners interviewed were raised by parents who were also business owners. Some of them also intend to work with their families and pass on entrepreneurial values to their children. This reinforces existing research

that highlights the importance of family tradition and support, especially in terms of readiness to work longer hours and providing childcare.

19

I don’t have any employees. My daughters help me out when they can.

— (Respondent 2)

I have maybe a decade, then I’ll hand it over to my son. He’s 14 and showing interest. We’ll see if he’s still interested after he graduates.

— (Respondent 29)

The contributions of small businesses were also stated in a recent similar study

20: “Described as the country’s economic “backbone”

21, small enterprises accounted for more than a third of Australia’s

gross domestic product in 2019.

22 In recent years they have created $414 billion of industrial value

23 and employed 44 percent of Australia’s workforce.

24

More than 97 percent of employing businesses are small businesses.25 These tiny economic building blocks are playing a huge role in Australia’s economic performance.”

Policy implications

Insights generated from the interviews of CaLD business owners highlights the importance of providing specific support and services and addressing some long-term institutional barriers. This report focuses more on the specific support and services such

as easily accessible information, credit and grants and networking opportunities as pathways to ensure equitable playing field for CaLD small business owners to grow, prosper and enhance their contributions to WA’s economy and society. It is

expected that proper implementation of the Western Australian Multicultural Policy Framework (WAMPF) endorsed by the Cabinet in February 2020 will help in addressing some of the institutional issues raised in this study in the long run.

Appropriate policies and services around information, networking and promotion

The research highlighted that CaLD business owners are making significant contributions in the business sector, creating jobs and niche markets, diversifying the economy and providing necessary services to local, regional, state, national and international

markets. Most of the respondents of this research were first generation migrants, who moved to Australia as students or as mature professionals. They experienced challenges such as culture shock due to different business norms and culture, difficulty

in building networks to enable business development, lack of adequate marketing nous and resources, as well as language barriers and experiencing discrimination.

To address these challenges and providing more support to encourage entrepreneurship, measures such as establishing a ‘one-stop-shop’ for migrant business owners, with a suite of online resources and ancillary support services including the

provision of translation services or information provided in multiple languages will be helpful. Types of support identified by the respondents that would be beneficial in their entrepreneurial pursuits include courses on financial literacy, Australian

business norms and business language as well as advice on how to access finance to start or expand their business and how to build a credit rating.

The government might consider acknowledging the contribution of migrant businesses and also promote business ownership as a viable and rewarding career path for CaLD migrants through media campaigns highlighting the advantages of becoming ‘your

own boss’. Migrant business awards could also be used to promote success stories and create business role models within CaLD communities, particularly among CaLD groups with lower levels of business ownership such as women and younger people.

Supporting CaLD sole traders to become employers

The research showed that a significant proportion (32.4%) of CaLD business owners interviewed were sole traders who did not employ any people. This group can be targeted with adequate resource, support and training, enabling them to expand their business,

thus generating employment for others. For example, a funding mechanism can be established to provide migrants with access to business loans to invest in technological resources to facilitate growth. They can be targeted to receive essential business

advice, as well as other services such as introducing migrants to relevant business associations, potential suppliers and customers. As three-quarters of respondents wished to expand their business over the next five years, targeting these people

and other similarly placed CaLD business owners could help create job opportunities for Western Australians. This would especially be beneficial for other people from CaLD backgrounds given that both the rates of unemployment and proportion not in

the labour force were higher for CaLD men (6.3% and 27.6%, respectively) and women (6.2% and 41.5%, respectively), compared to the state averages for men (5.4% and 24.4%, respectively) and women (4.4% and 35.1%, respectively).

Transforming migrants from ‘necessity-based’ to ‘opportunity-based’ entrepreneurs

Literature indicates that outcomes from businesses are better for opportunity-based entrepreneurs compared to necessity-based entrepreneurs. 26 Motivational narratives highlight external factors such as labour market conditions and other supportive

government policy measures available to migrant communities often impact the decision to start a business. Therefore, focus on creating supportive policies and strategies for migrant business owners can help create an equitable platform to be successful

in the business journey. These measures can include accessible and low-cost credit and grant facilities, an investment fund focused on long-term funding solutions for small businesses,27 technical and logistical support with space and IT

services, and easily accessible information in multiple languages through multiple communication channels such as radio, television and digital platform. Additionally, one of the essential actions that will benefit CaLD business owners is around the

area of building effective networks.

Areas for government to consider:

- greater and relevant networking opportunities for CaLD small businesses

- promotion and recognition of CaLD business owners

- easier access to financial support and wider markets.

Notes and references

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (June 2019). Businesses by main state, by industry class, by employment size ranges. Counts of Australian Businesses, including Entries and Exits, June 2015 to June 2019, accessed 17 August 2020.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020) ‘Estimated resident population, Country of birth, State/territory, Age and sex — as at 30 June 1996 to 2016, Census years’, People, Population, accessed 07 September 2020.

- Excludes SARs (Special Administrative Regions i.e., Macau & Hong Kong) and Taiwan

- Excludes 1.6% Year of Arrival — not stated

- Australian Government Department of Home Affairs, produced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics for the Department of Home Affairs https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/mca/files/2016-cis-italy.PDF

- Australian Government Department of Home Affairs, produced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics for the Department of Home Affairs https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/mca/files/2016-cis-vietnam.PDF

- Australian Government Department of Home Affairs, produced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics for the Department of Home Affairs) https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/mca/files/2016-cis-china.PDF

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade website. An India Economic Strategy to 2035, Navigating From Potential to Delivery. A report to the Australian Government by Mr Peter N Varghese AO https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/india/ies/pdf/dfat-an-india-economic-strategy-to-2035.pdf

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016). Business owners across Australia, Table 7. Counts of Business Owner Managers by Greater Capital City Areas (GCCSA), Age and Sex, 2016, Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia — Stories from

the Census, 2016, accessed 01 February 2021.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (June 2019). Businesses by main state, by industry class, by employment size ranges. Counts of Australian Businesses, including Entries and Exits, June 2015 to June 2019, accessed 17 August 2020.

- Ibid.

- They were selected with the help of business councils, community groups, social media including OMI’s Facebook page and other CaLD community or business pages as well as by contacting business owners from CaLD backgrounds in metropolitan and

regional LGAs. Both video conferencing and face-to-face methods were used.

- For literature and a detailed review, please refer to: Chen, L., Sinnewe, E., and Kortt, M. (2018). Evidence of Migrant Business Ownership and Entrepreneurship in Regions. Canberra: Regional Australia Institute. Min, P. G., & Bozorgmehr, M. (2003).

United States: The entrepreneurial cutting edge. In R. Kloosterman & J. Rath (Eds.), Immigrant entrepreneurs: venturing abroad in the age of globalization (pp.17-37). Oxford: Berg Volery, T. (2007). Ethnic entrepreneurship: a theoretical framework.

In L. Dana (Ed.), Handbook Of Research On Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship (pp. 30- 41). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Aspiration is often treated as a part of opportunity motivation, but here it is presented separately given that a large majority of respondents aspired to own business.

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) 2019/2020 Report. Available from https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-2019-2020-global-report

- Please refer to Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman (2018). Affordable capital for SME growth. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia

- OECD/European Union (2019), The Missing Entrepreneurs 2019: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3ed84801-en

- Out of 34 respondents, 23 (or 68%) were of Asian origin.

- The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia (2013) Canberra. Inquiry into Migration and Multiculturalism in Australia, Joint Standing Committee on Migration. https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/house_of_representatives_committees?url=mig/multiculturalism/report/fullreport.pdf. K Carrington, A McIntosh, and J Walmsley (2007). The Social Costs and Benefits

of Migration into Australia, University of New England and the Centre for Applied Research in Social Sciences (pp. 94–95).

- Trish Prentice (2021). From the far side of the world to the corner of your street. Scanlon Foundation Research Institute. https://scanloninstitute.org.au/sites/default/files/2021-03/Scanlon%20Institute_Essay%20Edition%203_final.pdf

- Deloitte (2020). COVID-19 Small Business Roadmap for Recovery & Beyond: Workbook. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/covid-19/au-deloitte-small-business-roadmap-for-recovery-and-beyond-workbook.pdf (p. 3) (last accessed 1 January 2021).

- Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman (2019). Small Business Counts: Small Business in the Australian Economy. https://www.asbfeo.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/ASBFEOsmall-businesscounts2019.pdf (p.5) (last accessed 1 January 2021).

- Parliament of Australia (2020). Small Business Sector Contribution to the Australian Economy. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1920/SmallBusinessSectorAustralianEconomy.

Industry Value Added or IVA refers to the total value of goods and services produced by an industry after deducting the cost. (last accessed 1 January 2021).

- Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman, “Small Business Counts”, 5.

- Ibid 7.

- Gabriela, C., Leonardo, I. and Laura, J. (2016). “Opportunity versus Necessity: Understanding the Heterogeneity of Female Micro-Entrepreneurs”. In World Bank Economic Review. Available from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/32234?show=full&locale-attribute=en

- For detailed recommendations on capital and funding, please refer to Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman (2018), Op.Cit

*Based on ABS 2020, Customised report *Country maps — Online Web Fonts

http://www.onlinewebfonts.com *World map —

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_map_without_Antarctica.svg

Case studies

Motivated to fulfill her dream of owning a business and to make a difference in the lives of young African women in WA

Case study: Rumbidzai Mudzengi was born in Zimbabwe and moved to Australia when she was 15 years old. She is now the owner of Anaka Glam, a make-up line catering to people with darker skin tones and Anaka & Co, a beauty and wellness company focused

on multiculturalism and mental health awareness.

Moving to Australia in her teens had been challenging. She felt there were no places for young African girls to go to for guidance on issues like depression and suicidal thoughts, both of which she had struggled with. She also noticed a lack of representation

in the beauty and hair industry for young women of her background. No one looked like her or knew enough to help her with make-up and hair for school events.

Rumbidzai knew early on that she wanted to have a business of her own. Having a father who was also an entrepreneur, she was exposed to what it takes to run a business. She decided to set up her first hair styling business at the age of 15.

She proceeded to get her make-up certificate and worked as a stylist in Canberra and Perth.In her years as a stylist, she found it difficult to find make-up products for herself and her clients and was surprised to meet veteran stylists of 20-25 years

who don’t know how to do make-up for Africans. She recognised an opportunity to do something she’s passionate about and launched her own make-up line, Anaka Glam in 2015.

Conversations with her clients and what they are going through and recognising the same issues she went through when she was young, Rumbidzai made it her mission to empower the multicultural community, especially young African women. This led to the launch

of her beauty and wellness business, Anaka & Co three years later in 2018, which specialised in wellness workshops.

Rumbidzai holds workshops and events to provide a space for women of colour to share their stories and raise mental health awareness in the community. When asked what her personal goals are in the next five years, she answered “I’d like to

write a book someday. But most of my personal goals are all tied to my work. I want to leave a legacy for my community that really focuses on representing young black women and help them increase their self-esteem and confidence.”

I want to leave a legacy for my community that really focuses on representing young black women and help them increase their self-esteem and confidence.

Resilient and optimistic despite an unsuccessful first business venture

Case study: Prabhjot Singh Bhaur was born in a small town in northern India and moved to Australia to study in 2007. He now owns Indian/Malaysian restaurant Avon Spice in Northam.

Prabhjot grew up in a small country town in the northern part of India, where his family had a dairy farm and flour mills. He moved to Melbourne in 2007 to get a degree in graphic design. He initially found learning the language challenging and experienced

culture shock. “When I compare Australia to where I came from, everything is different. I had to find my way around.” His brother moved to Perth in 2009 as Prabhjot was finishing his degree and he decided to move west as well to be closer

to family.

When I compare Australia to where I came from, everything is different. I had to find my way around.

In Perth, Prabhjot worked his way up from warehouse assistant to deputy warehouse manager. His hard work was further rewarded when the company asked him to move to Melbourne to be the operations manager of a new branch they were opening. But family is

very important to Prabhjot and despite his success in Melbourne, he decided to move back to Perth to be with his brother and to settle down with his wife.

After working in a similar role, he decided to invest in a car detailing franchise with his brother, thinking this would be easier to manage given it was his initial attempt at being a business owner. Unfortunately, things didn’t go very well on

his first business venture.

Despite having a rough start, he remained open to exploring new opportunities and take on new business ventures.

When he saw the franchise wasn’t going to work, he started looking for another business that would be smaller and friendlier. He and his brother found Avon Spice in Northam and bought it from the previous owners. He also started an import business

where he works with his brother who handles the accounting side of things. In addition to this, he studied real estate and has a license for that as well. “My advice to any small business owner who is starting is, don’t give up. You will

get a rough ride in the beginning or you might get lucky. But if you give up, that’s the end of the road. Just keep going.”

From job hunting difficulties due to lack of local work experience, to providing training and local work placements

Case study: Yvonne Yeo was born in Malaysia and moved to Australia to study in 1988. She now owns registered training organisation Australian Institute of Workplace Training (AIWT) catering to local and international students.

Yvonne Yeo grew up in Malaysia and chose to continue her university and post graduate studies in Perth in 1988. Despite becoming a permanent resident and completing a degree from an Australian university, she still found it challenging to find work. “Initially,

it was hard to get a job as jobs required Australian experience. Obviously, as a new migrant, it was hard because you need to get that first job, but you can’t because you don’t have Australian experience.” She decided to leave Perth

for Hong Kong to work for a couple of years.

Initially, it was hard to get a job. Jobs required Australian experience. Obviously, as a new migrant, it was hard because you need to get that first job, but you can’t because you don’t have Australian experience.

Yvonne was able to secure employment when she went back to Perth in 1996 and spent the next few years building her career. She worked her way up from being an accountant to being the chief financial officer and retired in 2016. Immediately after leaving

work however, she realised retirement didn’t suit her. At the time, she also didn’t want to look for a new role. She decided to go into business instead.

She purchased Australian Institute of Workplace Training (AIWT) in 2017. Her organisation provides courses and traineeships to school-leavers, people re-entering the workforce and mature professionals. Yvonne, being a former international student herself,

is using her background and experience to cater to both international and domestic students.

Other than navigating through the uncertainty of a pandemic, closed borders and its financial repercussions, Yvonne continues to manage the daily challenges of operating a Registered Training Organisation (RTO). However, Yvonne is an optimist and believes

opportunities can be found if you are open to them. With innovation, a great team, diligence and determination, Yvonne is looking to grow AIWT despite all the hurdles in the economy and the international training sector.

Two generations serving as bridges between Netherlands andAustralia

Case study: Jeff van Altena is a second-generation CaLD small business owner born in Sydney. He moved to Perth in 2001 and now owns and runs The Dutch Shop in Guildford.

Jeff van Altena was born to Dutch migrant parents who moved to Sydney in 1964. His family has been in the importing business for decades and specialise in Dutch goods.

After working on many different things, he decided to set up his own shop. He used his house as collateral to fund his dream, took up a small business course and asked his parents to be his suppliers, which they agreed to. “It’s well entrenched

in the blood. We’re importers by trade. It’s my own business but we’re heavily linked. There aren’t many Dutch products in Australia that don’t pass through us.”

It’s well entrenched in the blood.We’re importers by trade. It’s my own business but we’re heavily linked.

Initially, it was difficult to make Dutch people in WA aware his shop existed through advertising. He mentioned word of mouth was difficult to begin with, but his reputation grew from having a good range of products. “People are more hesitant about

dealing with small, independent businesses. Initially, there were some problems assuring clients. We import our own products. My parents have a good reputation, they have shops, and they supply the whole country.”

The Dutch Shop has one casual employee, but Jeff hopes to hire more in the next five years if the business and market conditions remain. His shop is well-known especially in the Dutch community, with clients — mostly expats who grew up with his products,

coming from all over Western Australia.

Despite cash flow challenges and the high cost of utilities, he enjoys the freedom of being his own boss. “The best thing about setting up a small business in Australia is freedom. Things are challenging and they remain to be challenging. But there’s

freedom and I do like being the captain.”

Appendices

Appendix 1: Overview of respondents’ background

| Gender | Ethnicity | Industry | Number of employees | Year in business | Educational background |

| Female | Kenyan | Other services | 0 | 2013 | Bachelor |

| Female | Norwegian | Real estate | 0 | 2015 | Not disclosed |

| Female | Malaysian | Education | 0 | 2018 | Not disclosed |

| Female | Indian | Professional services | 0 | 2014 | Bachelor |

| Male | Indian | Professional services | 24 | 2012 | Postgraduate |

| Female | Malaysian | Health care | 0 | 2010 | Bachelor |

| Female | Malaysian | Education | 25 | 2017 | Bachelor |

| Male | South Korean | Professional services | 2 | 2015 | Postgraduate |

| Male | South Sudanese | Media and telecommunications | 2 | 2013 | Bachelor |

| Male | Pakistani | Education | 6 | 2019 | Bachelor |

| Female | Indian | Other services | 4 | 2013 | Bachelor |

| Male | Chinese | Professional services | 5 | 2015 | Bachelor |

| Male | Indian | Professional services | 20 | 2015 | Bachelor |

| Male | Indian | Hospitality | 10 | 2018 | Bachelor |

| Female | Vietnamese | Wholesale trade | 0 | 2015 | Bachelor |

| Female | German | Education | 0 | 2010 | Bachelor |

| Male | Indian | Education | 25 | 2015 | Postgraduate |

| Male | Iranian | Professional services | 26 | 2018 | Postgraduate |

| Male | Singaporean | Real estate | 1 | 2018 | Bachelor |

| Female | South Korean | Education | 0 | 2010 | Bachelor |

| Male | Danish | Professional services | 0 | 2018 | Bachelor |

| Male | Malaysian | Professional services | 15 | 2015 | Bachelor |

| Male | Indian | Hospitality | 3 | 2019 | Bachelor |

| Male | French | Hospitality | 2 | 2015 | Not disclosed |

| Male | Italian | Real estate | 30 | 2004 | Bachelor |

| Female | Thai | Education | 0 | 2014 | Postgraduate |

| Male | Bangladeshi | Hospitality | 3 | 2020 | Bachelor |

| Male | Dutch | Retail trade | 1 | 2005 | Not disclosed |

| Male | Slovakian | Professional services | 10 | 2004 | Postgraduate |

| Male | Indian | Other services | 0 | 2018 | Postgraduate |

| Female | Indian | Education | 0 | 2008 | Postgraduate |

| Female | Zimbabwean | Other services | 2 | 2019 | Not disclosed |

| Male | English* | Professional services | 1 | 2003 | Not disclosed |

| Female | Filipina | Other services | 0 | 2020 | Not disclosed |

For partial list of respondents, please see the acknowledgements.

*Cypriot background

Appendix 2: Matrix table on business motivation by background information of CaLD small business owners

| Sole trader or employer | Gender | Industry | Ethnicity | Motivations |

|---|

| Sole trader | Female | Education | Malaysian | Freedom, flexibility and child caring opportunity |

| Employer | Male | Professional services | South Korean | Aspiration |

| Employer | Male | Education | Pakistani | Aspiration and preparedness to take risks |

| Employer | Male | Professional services | Chinese | Aspiration |

| Employer | Male | Professional services | Indian | Aspiration, qualification |

| Employer | Male | Education | Indian | Aspiration |

| Employer | Male | Real estate | Singaporean | Aspiration |

| Employer | Male | Hospitality | Indian | Aspiration and family tradition |

| Employer | Male | Hospitality | French | Aspiration |

| Employer | Male | Real estate | Italian | Aspiration |

| Sole trader | Female | Education | Thai | Aspiration, skills |

| Employer | Male | Hospitality | Bangladeshi | Aspiration, experience and skills/qualifications |

| Employer | Male | Retail trade | Dutch | Aspiration and family tradition |

| Employer | Male | Professional services | Slovakian | Aspiration |

| Sole trader | Male | Other services | Indian | Aspiration, experience and skills/qualifications |

| Employer | Female | Other services | Zimbabwean | Aspiration, experience and skills/qualifications |

| Employer | Male | Professional services | English* | Freedom, flexibility and family time |

| Sole trader | Female | Other services | Filipina | Aspiration, experience and skills/qualifications |

| Employer | Female | Professional services | Indian | Not intentional, personal or opportunity driven |

| Sole trader | Female | Health care | Malaysian | Not intentional, personal or opportunity driven |

| Employer | Male | Media and telecommunications | South Sudanese | Not intentional, personal or opportunity driven |

| Sole trader | Female | Education | German | Opportunity |

| Employer | Male | Professional services | Iranian | Personal, opportunity +qualification |

| Sole trader | Female | Education | South Korean | Not intentional, personal or opportunity driven |

| Employer | Male | Professional services | Danish | Not intentional, personal or opportunity driven |

| Employer | Female | Other services | Indian | Altruism, contribute to |

| Employer | Male | Hospitality | Indian | Altruism, contribute to + family tradition |

| Sole trader | Female | Real estate | Norwegian | Need, loss, no adequate job, discriminated |

| Employer | Male | Professional services | Indian | Loss, no, adequate job, "not an easy choice" |

| Employer | Female | Education | Malaysian | Need, loss, no, adequate job |

| Sole trader | Female | Wholesale trade | Vietnamese | Lack of adequate job |

| Employer | Male | Professional services | Malaysian | Need, loss, no, adequate job |

| Sole trader | Female | Education | Indian | No job opportunity, not much business idea |

*Cypriot background

Acknowledgements

OMI would like to thank all respondents of the research including:

- Yvonne Larsen, Chief Executive Officer of Nauti Picnics

- Linette Devigan, Entrepreneur

- Nilesh Makwana, Chief Executive Officer of Illuminance Solutions

- Yvonne Yeo, Chief Executive Officer of Australian Institute of Workplace Training

- Tommy Shin, Chief Executive Officer of Lateral Capital Ventures

- Peter Deng, Founder and Chief Executive Officer of Africa World Books

- Mahmood Hussein, Chief Executive Officer of Global Drone Solutions

- Narinder Kaur, Director of Connect Migration Solutions

- Alex Shi, Director of Perth Beijing Translation and Interpreting Services

- Rupen Kotecha, Chief Executive Officer of Western Australian Leaders

- Ashish Chibba, Founder and Director of Street Eats Eatery

- Jenny Trinh, Director of AA EXIM

- Sandra Beck, Director and Founder of Internships Perth International

- Hari Sethi, Founder and Principal Executive Officer of NIT Australia

- Behrad Izadi, Co-founder and Senior Cloud Architect of TechTiQ

- Ebony Bae, Founder and Teacher of Korean Language Cultural Education Center

- Brian Ambrosius, Owner of GOTO Yeah

- Bryan Ho, Director of BHO Interiors

- Prabhjot Singh Bhaur, Owner of Avon Spice

- Louis Boeglin, Owner of Louis Boeglin Patisserie

- Joseph Rapanaro, Owner of SVN | Perth

- Krongkarn Boonyapapong, Director and Teacher of Thai Teaching Perth

- Simon Mohiuddin, Owner of Simon Says

- Jeff van Altena, Owner of The Dutch Shop

- Nutan Shukla, Founder and Program Director of Draw ’n’ Learn

- Rumbidzai Mudzengi, Owner of Anaka & Co & Anaka Glam

* Eight respondents opted to remain anonymous